The Shadow of the Nineteenth Century: Rider Haggard and Tolkien

One of the books I read in 2020 was She, by H. Rider Haggard (1887). I thoroughly enjoyed it, as being an exemplar of a good old-fashioned adventure story. I also noted with amusement the influence it had on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Seriously. Compare the respective climaxes – it is blatant.

But one other influence the book clearly had in later media? J.R.R. Tolkien. To a degree that genuinely surprised me.

Having now also done a follow-up re-read of another of Rider Haggard’s works, King Solomon’s Mines (1885), I thought I would look at the way these two Victorian adventure books wound up influencing Middle-earth. I am far from the first to notice the connection – see the Wikipedia page on Tolkien’s modern influences – but with the earlier author still fresh in my mind, I thought it appropriate fodder for a blog article. It is worth remembering that Tolkien was not simply channelling Beowulf, the Eddas, and Kalevala in his creative work, but that he was also interacting with more recent material.

She (1887)

There is a case for seeing She as a cornerstone of early Modern Fantasy – there are bona fide supernatural elements, and the tropes it uses show up in so much of subsequent literature. On the other hand, it is a classification with which I personally disagree. Much as Shelley’s Frankenstein gets anachronistically shoe-horned into the science-fiction genre, She is not fantasy in itself. She is very definitely an Adventure Yarn with fantastical elements… which just happened to anticipate what would happen later. You can see how Rider Haggard feeds through into E.R. Burroughs’ Barsoom, and thence into inter-war sword and sorcery, but Rider Haggard was working in the shadow of the non-fantastic Treasure Island. Modern Fantasy as we recognise it would have to wait for William Morris.

But wait… I was talking about J.R.R. Tolkien, wasn’t I? By good fortune, She is one of the handful of books that Tolkien explicitly acknowledges as an influence. In a 1966 interview with Henry Resnick, Tolkien remarked:

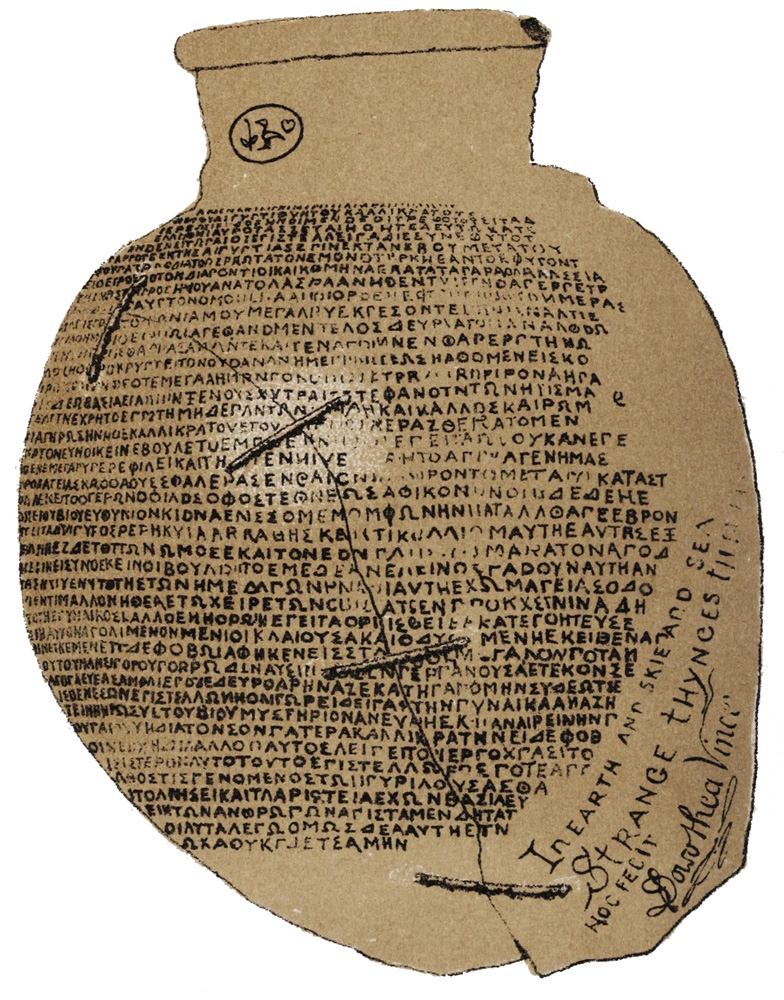

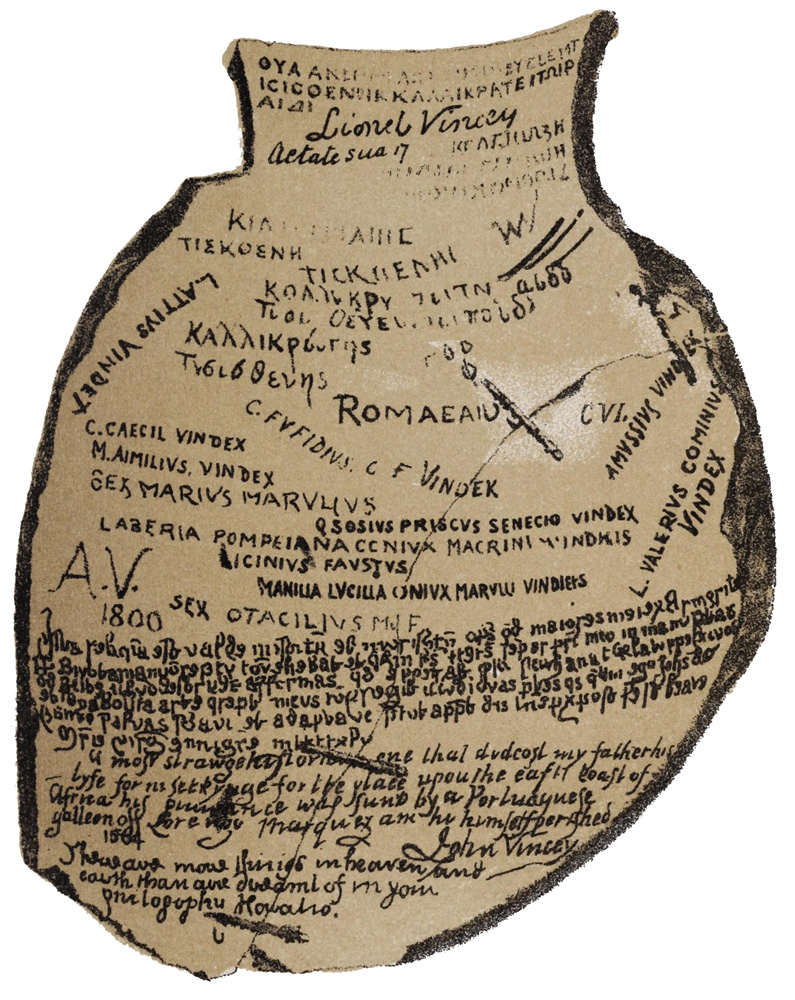

I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas], which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving.

The shard of Amenartas is a purported ancient text, included by Rider Haggard as a means of providing some exposition to the story. Well and good. It is the incident that incites the start of the adventure. But the shard is no ordinary ancient text, at least in terms of presentation. Rider Haggard gives facsimiles of the fragment, in actual Greek:

And Latin. And Early Modern English:

Don’t worry. Rider Haggard helpfully transcribes and translates the text. But the sheer effort the author went to, in terms of making the artefact look real and believable is noteworthy. It rather recalls the One Ring inscription, and the inscription on Balin’s Tomb, not to mention in-universe Tolkienian texts like The Book of Mazarbul and Thror’s Map. In terms of actual historical exposition, there is also a decent comparison between Rider Haggard’s protagonists puzzling out the Shard, and Gandalf learning about the Ring via the forgotten Scroll of Isildur in the archives of Minas Tirith.

(Yes, I am aware that Rider Haggard did not invent this trope. Jules Verne provides a runic manuscript in A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1871). But Tolkien cites Rider Haggard, not Verne).

There are also several other apparent influences of the book on Tolkien. For ease of discussion, I will now cover them in turn:

(i) Kôr

Perhaps the single cheekiest Tolkienian shout-out to Rider Haggard is the city of Kôr. In She, the city of Kôr is an ancient ruined city, so ancient that it was already long abandoned when Ayesha turned up, thousands of years before the narrative begins. Kôr predates the Egyptians, in terms of antiquity, and it adds some glorious atmosphere to the setting.

It may therefore interest you to know that Kôr was the original name of the great Noldorin city, Tirion upon Túna. The home of Finwë, Fëanor, et al. Moreover, in Tolkien’s initial conception – found in The Book of Lost Tales – the city ends up abandoned. An early Tolkienian poem, titled Kôr: In a City Lost and Dead, describes the scene, after the Elves have left it.

“A sable hill, gigantic, rampart-crowned

Stands gazing out across an azure sea

Under an azure sky, on whose dark ground

Impearled as ‘gainst a floor of porphyry

Gleam marble temples white, and dazzling halls;

And tawny shadows fingered long are made

In fretted bars upon their ivory walls

By massy trees rock-rooted in the shade

Like stony chiseled pillars of the vault

With shaft and capital of black basalt.

There slow forgotten days for ever reap

The silent shadows counting out rich hours;

And no voice stirs; and all the marble towers

White, hot and soundless, ever burn and sleep.”

This poem was actually written in 1915 (see The Book of Lost Tales, Volume I, p.136.), before Tolkien had even started on what we now know as the legendarium. To call it fanfiction would be crass, but there is a sense that Tolkien was using Rider Haggard’s Kôr as an inspirational jumping-off point for his own imaginative efforts – as though he wants to provide the ‘true’ story of an ancient city. One built by Elves, not Men, and one not abandoned because of a mere plague (as in Rider Haggard), but for other reasons. And because this is J.R.R. Tolkien we are talking about, he also justifies the name of the city via his own invented languages, in much the same way that his Quenya name for a certain Second Age Island invokes Atlantis: http://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/K%C3%B4r

In terms of the later Tolkien mythos, I cannot help but think that Moria and Osgilliath both owe a bit to Rider Haggard’s Kôr. Both are ancient ruins by the time of the narrative, with the former featuring copious dark tunnels after the manner of the Tombs of Kôr, and the latter having been decimated by a plague, much like Rider Haggard’s city was destroyed.

(ii) Galadriel and Shelob

Rider Haggard’s Ayesha is one of the more memorable villains in adventure literature. She not only gives the book its literal title (She), but the expression She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed has entered the wider English language.

She – the character – is also clearly an influence on two rather distinct characters, Galadriel and Shelob. The former has Ayesha’s glamour, as the beautiful and immortal sorceress, who has ruled her strange little domain for millennia with little influence from the outside world. Indeed, a cheeky summation of Rider Haggard’s book would be what would happen if Galadriel had set up shop in the ruins of Moria (minus Balrog), waiting centuries for Peregrin Took (yes, really) to turn up, as the reincarnation of her lost love. Ayesha is dark-haired, however, not a blonde like Galadriel, which given Tolkien’s own tendency to use dark hair and grey eyes (a la his wife, Edith) as a shorthand for beauty, is an interesting change.

The other Galadriel feature that might well owe something to Ayesha is the Mirror. The Mirror of Galadriel is a basin of water that shows our protagonists a variety of visions. Ayesha meanwhile has her own version:

“Then gaze upon that water,” and she pointed to the font-like vessel, and then, bending forward, held her hand over it.

I rose and gazed, and instantly the water darkened. Then it cleared, and I saw as distinctly as I ever saw anything in my life—I saw, I say, our boat upon that horrible canal. There was Leo lying at the bottom asleep in it, with a coat thrown over him to keep off the mosquitoes, in such a fashion as to hide his face, and myself, Job, and Mahomed towing on the bank.

I started back, aghast, and cried out that it was magic, for I recognised the whole scene—it was one which had actually occurred.

“Nay, nay; oh Holly,” she answered, “it is no magic, that is a fiction of ignorance. There is no such thing as magic, though there is such a thing as a knowledge of the secrets of Nature. That water is my glass; in it I see what passes if I will to summon up the pictures, which is not often. Therein I can show thee what thou wilt of the past, if it be anything that hath to do with this country and with what I have known, or anything that thou, the gazer, hast known. Think of a face if thou wilt, and it shall be reflected from thy mind upon the water. I know not all the secret yet—I can read nothing in the future….”

Much as Samwise Gamgee interprets Galadriel’s actions as magic, to a degree that Galadriel finds vaguely puzzling, here we have our protagonist talk of magic to Ayesha. The difference is that Ayesha admits that her powers are comparatively limited, as Holly straight-out tells us later:

For it must be remembered that She’s power in this matter was strictly limited; she could apparently, except in very rare instances, only photograph upon the water what was actually in the mind of some one present, and then only by his will.

Galadriel’s power stays much more mysterious, of course. Tolkien would not ruin the effect by comparing her Mirror to photography!

But Ayesha is a villain, and Galadriel is not, though she obviously has it in her. The darker side of Ayesha arguably manifests itself in Shelob. Quite apart from the very name inviting comparisons (She/Shelob), with Gollum even using the term ‘She’ during his little debate, Ayesha lives in the dark tunnelled tombs of abandoned Kôr. Shelob lives in the dark tunnels of Cirith Ungol. While Ayesha does not actually eat people, she is territorial and a murderer, and her relationship with the local tribes rather evokes the fearful respect the local Orcs have for “Her Ladyship”. Billali could even pass for a less mad and less malevolent Gollum-figure.

(iii) The Bridge Over the Abyss

The comparisons between Tolkien’s Moria and Rider Haggard’s Kôr do not stop at both being ancient and abandoned relics of civilisations. Both of them have a Bridge over an apparently bottomless abyss, albeit Tolkien’s is man-made (or, rather, dwarf-made), and Rider Haggard’s is actually a natural formation:

Ayesha called to us, and we crept up to her, for she was a little in front, and were rewarded with a view that was positively appalling in its gloom and grandeur. Before us was a mighty chasm in the black rock, jagged and torn and splintered through it in a far past age by some awful convulsion of Nature, as though it had been cleft by stroke upon stroke of the lightning.

This chasm, which was bounded by a precipice on the hither, and presumably, though we could not see it, on the farther side also, may have measured any width across, but from its darkness I do not think it can have been very broad. It was impossible to make out much of its outline, or how far it ran, for the simple reason that the point where we were standing was so far from the upper surface of the cliff, at least fifteen hundred or two thousand feet, that only a very dim light struggled down to us from above.

The mouth of the cavern that we had been following gave on to a most curious and tremendous spur of rock, which jutted out in mid air into the gulf before us, for a distance of some fifty yards, coming to a sharp point at its termination, and resembling nothing that I can think of so much as the spur upon the leg of a cock in shape. This huge spur was attached only to the parent precipice at its base, which was, of course, enormous, just as the cock’s spur is attached to its leg. Otherwise it was utterly unsupported.

“Here must we pass,” said Ayesha. “Be careful lest giddiness overcome you, or the wind sweep you into the gulf beneath, for of a truth it hath no bottom;” and, without giving us any further time to get scared, she started walking along the spur, leaving us to follow her as best we might. I was next to her, then came Job, painfully dragging his plank, while Leo brought up the rear. It was a wonderful sight to see this intrepid woman gliding fearlessly along that dreadful place. For my part, when I had gone but a very few yards, what between the pressure of the air and the awful sense of the consequences that a slip would entail, I found it necessary to go down on my hands and knees and crawl, and so did the other two.

There are differences, of course. Tolkien’s Bridge is fifty feet, whereas Rider Haggard’s is fifty yards. Moreover, Rider Haggard’s Bridge does not actually extend the full-way across. It turns out that one needs to carry a plank to bridge the rest of the way. When the plank falls into the abyss, our protagonists find themselves stuck trying to cross what amounts to a broken bridge over an endless drop. Tolkien’s Bridge also breaks, but in an actually advantageous way, since it takes out the Balrog, and makes it harder for the Orcs to pursue the fleeing Fellowship.

It is worth pointing out that Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade also utilises the Bridge Over the Abyss trope, though as we shall see, the comparisons with that keeping coming too…

(iv) Immortality and Its End

Recall the purpose of the Great Rings in Tolkien – they slow down time, and enable the Elves to continue living in an unchanging world. Galadriel’s Realm is sustained via the power of Nenya, one of the Three. When a mortal gets his hands on a Great Ring… they find themselves similarly unchanged, though that has consequences, as the Ringwraiths or Gollum could tell you.

The Destruction of the One Ring ends all that is done with the Great Rings. Galadriel’s Realm has time wash over it. The Ringwraiths finally die (presumably because time has finally caught up with them after more than four thousand years). Bilbo Baggins ages dramatically. And Gollum? We obviously never get to see the effects of the Ring’s destruction on him, but he offers a poignant prediction:

We’re lost. And when Precious goes we’ll die, yes, die into the dust. ‘ He clawed up the ashes of the path with his long fleshless fingers. ‘Dusst!’

Gollum has not studied Ring lore, yet somehow his long possession has given him an insight. Those 478 or so missing years are going to suddenly catch up with him… dust indeed.

Now the common modern visualisation of sudden and rapid ageing is the famous scene at the end of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (which terrified me when I was a child). But it is actually a very old trope. Rapid ageing shows up in Irish myth, as in the Immram story, The Voyage of Bran, or in the later tale of the Land of Youth. And Tolkien would have been aware of the mythic and folkloric precedents.

But it also shows up in She.

SPOILERS…

It turns out that Ayesha is not naturally immortal. She has been granted her unchanging longevity (and apparent youth) via bathing once in magical fire. And she wants to share this with our protagonists, whom she also wishes to live forever. To demonstrate how safe this is, she bathes a second time.

It turns out that bathing a second time removes the effects of the first time. So Ayesha goes from being young and beautiful to showing her true age. Which is several millennia…

Ouch.

Our protagonists decide against bathing even once, because they would much rather accept their own natural mortality than engage in this twisted form of immortality. A sentiment that Tolkien himself spent much of his own work articulating.

(v) The Party

A minor point, but in rounding out my comparisons between She and The Lord of the Rings, I would note that the initial trio who set out from Bag End – Frodo Baggins, Samwise Gamgee, and Peregrin Took – actually correspond pretty well to the three English protagonists in She. Frodo maps onto Holly, middle-class, and well-educated in ancient lore and language. Sam is Job, the loyal, honest, yet occasionally mistrustful working-class servant. Pippin is Leo, the himbo aristocrat of the group.

These character archetypes were in use long before Rider Haggard, of course, but I do think the comparison is worth mentioning.

King Solomon’s Mines (1885)

I have discussed potential influences of She on Tolkien at some length, but what of another of Rider Haggard’s famous Victorian Adventure novels, King Solomon’s Mines? This one lacks the overt fantastical elements of She, albeit there is maybe a hint of something unnatural going on with Gagool’s age. And unlike She, we have no explicit confirmation that Tolkien actually read it.

There are, however, some comparisons that could be drawn, even if they are not as clear-cut as the other novel. We don’t have anything quite as elaborate as the shard to incite the adventure, but Rider Haggard does furnish us with a map, which is at least vaguely Tolkienian. Anyway, on with some suggested similarities…

(i) Gollum and Gagool

Gagool the horrid and incredibly aged wise-woman is arguably one of the influences for Gollum. Not so much in terms of personality, since Gagool is at least sane, but rather in terms of physical appearance and a certain plot point she is involved with.

Much like Gollum, Gagool is ancient by mortal standards, to a degree where no-one – including the most aged of her people – can remember her as being anything other than elderly. She talks of events of three centuries past as though she remembers them personally, and while she may be lying (she is highly treacherous), there is the sense that there is something indeed supernatural going on. And like Gollum, she is hideous, small, and shrivelled. Something that no longer looks quite human, though which is still more than willing to cling onto the very dregs of a desiccated existence.

As for the plot point….

SPOILERS

Gagool is forced to lead our protagonists to the fabled treasure chamber of Solomon, since only she knows the way. She opens a hidden door, and waits until our protagonists are inside the chamber. While the protagonists are mesmerised by the gold and diamonds, Gagool treacherously abandons them by closing the door. The door in question is a huge wall of solid rock that ascends and descends from the ceiling.

Gagool does not quite escape, however, since she is herself trapped under the door, and crushed into pudding. No-one really misses her, though our trapped protagonists have other concerns, what with now being entombed in solid rock.

I think one can see an analogy with Gollum promising to lead Frodo and Samwise through to Mordor, only to treacherously abandon them in Shelob’s Lair. Gollum, however, manages to live another day, and though he too pays for his treachery, at least he isn’t eaten by Shelob.

(ii) Eat the Treasure

If She and The Lord of the Rings both explore facsimile immortality, King Solomon’s Mines and The Hobbit both share a warning against greed. A major point of the later Hobbit is Thorin caring about treasure more than is healthy, eventually culminating in a notable exchange:

‘I declare the Mountain besieged. You shall not depart from it, until you call on your side for a truce and a parley. We will bear no weapons against you, but we leave you to your gold. You may eat that, if you will!’

One cannot eat gold, of course. Bilbo is understandably distraught at the prospect.

Now consider the malevolent Gagool, speaking to our protagonists as they stand agape at the diamonds of Solomon’s Treasure Chamber:

‘Hee! hee! hee!’ went old Gagool behind us, as she flitted about like a vampire bat. ‘There are the bright stones that ye love, white men, as many as ye will; take them, run them through your fingers, eat of them, hee! hee! drink of them, ha! ha!’

Gagool is telegraphing our protagonist’s fate, by taunting them: one cannot eat or drink diamonds, any more than one can eat or drink gold, so wealth matters little when you are trapped. As with Thorin and Company, Allan Quatermain and his friends are to learn the hard way that there are more important things in life than treasure. And in both cases, the warning carries the same mocking phraseology.

(Both do learn, of course. Just as Bilbo realises he can’t take a fourteenth share of the Hoard back home with him, and contents himself with a chest of gold and a chest of silver, so Quartermain decides against excessive looting, and goes home with a modest number of diamonds. It still makes him a wealthy man).

(iii) The Acquired Hidden Heir

In referring to the protagonists of She, I noted that they map fairly well onto the initial protagonists of The Lord of the Rings. The same cannot really be said of King Solomon’s Mines, with one notable exception.

Both parties pick up an unplanned-but-useful extra. King Solomon’s Mines sees a chap called Umbopa join the expedition. Ostensibly as a servant, but we soon realise he’s rather more than that. He’s Ignosi, the rightful King of the country they are travelling to, and a fair amount of the story deals with the challenges of restoring him to the throne. In short, he plays a similar sort of role to Tolkien’s Aragorn, who goes from being a mere Ranger Guide at Bree, to being the returned King in Minas Tirith.

(Denethor is hardly Twala though, and neither is Boromir Scragga).

Hidden Heirs are, of course, an ancient and well-worn trope, and there is no reason to think that Aragorn was influenced by Umbopa/Ignosi any more than by countless other stories. However, as with the She trio, I just thought the comparison was worth mentioning in passing.

(iv) The Awkward Englishman in Chain-mail

I have earlier suggested that King Solomon’s Mines actually has some similarities with The Hobbit, rather than The Lord of the Rings. So in rounding out my discussion of the book, I thought I would point out one last comparison. A relatively minor one, but still:

The Hobbit’s protagonist, Bilbo Baggins is gifted the famous (and useful) mithril shirt by Thorin. His immediate thought is that he looks absurd (albeit magnificent), because Bilbo is at heart a Victorian gentleman. He also winds up being knocked out in a subsequent battle, because while he’s clever, and good at throwing things, he is not much use in genuine combat.

The narrator of King Solomon’s Mines, Allan Quatermain, and his companions are gifted chain-mail shirts before a battle. One of those companions, Sir Henry, takes to it like a duck to water, but Quartermain and Captain Good are notably more awkward. Good carefully tucks his chain-mail shirt into his pair of “very seedy” corduroy trousers, giving rise to the sort of comic relief you see with Bilbo wearing armour. As a bonus, Quartermain gets knocked out in a subsequent battle, because while he’s clever, and excellent with a rifle, he’s not much use when ammunition is scarce, and fierce warriors are charging at him.

I think the comparison arises less because Tolkien was deliberately channelling King Solomon’s Mines when he writing The Hobbit, and more because it is an inevitable consequence of putting Victorian gentlemen in an technologically ‘older’ and more heroism-focused world. The temptation to play the juxtaposition for comic relief is simply too great to pass up.

**

Phew. A fairly lengthy post to start the year, and one that is not exactly breaking new ground in Tolkien analysis. Nevertheless it is one that suggested itself in light of last year’s reading material. As you can see, She has a much better claim at being a Victorian precursor to Middle-earth, which is only appropriate given that Tolkien himself cited it, though King Solomon’s Mines is not without potential points of comparison. On my re-read of the latter, I was indeed struck by the line about eating diamonds, and how well it fitted with the themes of The Hobbit.

Anyway, if you haven’t read the Rider Haggard works in question, I can strongly recommend them. A bit dated in some respects (they were published in 1885 and 1887, after all), but there is much worse out there.

I think the case is made. I’d just point out, the Kor poem reads a lot like ‘The City in the Sea’. Perhaps it was sparked by Poe’s line “Death looks gigantically down”.

JRRT at his worst was a truly terrible poet. These lines fall like lead, imagine Vincent Price having to read them:

Like stony chiseled pillars of the vault

With shaft and capital of black basalt.

LikeLiked by 2 people

To be fair, he was 23 when he wrote them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Le livre du jour : She par Henry Rider Haggard – Mattchaos88

I’ve yet to work out what a pingback is but here is Mattchaos’s one on this article:

https://mattchaos88.wordpress.com/2021/08/20/le-livre-du-jour-she-par-henry-rider-haggard/

Je ne suis pas le premier à l’avoir remarqué, il parait même que Tolkien ne s’en est pas caché, mais je n’étais jamais tombé sur cette information. Je savais que Tolkien s’était inspiré de légendes anglo-saxonnes et nordiques, l’anneau des Nibelungen, les nains, les elfes, le concept du Terre du milieu (Midgard), des récits classiques et anciens. Mais j’étais loin de m’imaginer Tolkien capable ou désireux de s’inspirer de quelque chose d’aussi commun qu’un roman d’aventure.

English courtesy Google Translate which seems alarmingly good these days:

I was not the first to notice it, it even seems that Tolkien did not hide it, but I had never stumbled upon this information. I knew Tolkien had drawn inspiration from Anglo-Saxon and Norse legends, the ring of the Nibelungen, dwarves, elves, the concept of Middle Earth (Midgard), classical and ancient tales. But I was far from imagining Tolkien able or willing to draw inspiration from something as common as an adventure novel.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Cheers. A pingback is simply a notification that an article is linking to one of yours – it’s a way of following up someone who is referencing you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I just finished ‘King solomon’s Mines’. On reading how Good survives a spear attack because he is wearing the very fine chain mail that was gifted to him, I immediately thought of Frodo and his mithril shirt. I then looked up Tolkien influences and discovered H R Haggard prominently listed. Which some how brought me to this blog. I believe there is a direct link between Hagard’s chain mail and the mithril vest in Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings. Thank you very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person